A Road Trip with Failure: A Conversation with Sasha West

February 6, 2014, by Beth Lyons

On Friday, February 7, Sasha West and Jason Schneiderman will read their poetry at the Menil Collection as part of the Public Poetry series. West will be reading from her collection Failure and I Bury the Body and Schneiderman from his collection Striking Surface.

On Friday, February 7, Sasha West and Jason Schneiderman will read their poetry at the Menil Collection as part of the Public Poetry series. West will be reading from her collection Failure and I Bury the Body and Schneiderman from his collection Striking Surface.

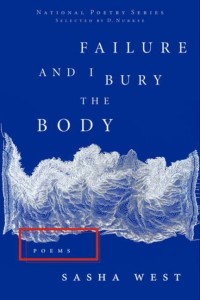

Sasha has a close relationship with Inprint. She was a winner of the Inprint Paul Verlaine Prize and was a long time Inprint Writers Workshop instructor. She is an alumnus of the University of Houston Creative Writing Program, where she also served as the editor for Gulf Coast: A Journal of Literature and Fine Arts, and later went on to become Gulf Coast’s Board President. In 2012, West’s poetry collection, Failure and I Bury the Body, was selected by D. Nurske as a winner of the National Poetry Series and published by Harper Perennial.

Her poems have appeared in Southern Review, Ninth Letter, Third Coast, and others. Sasha was kind enough to answer some questions about her poetry and creative process—a big thanks to Sasha for taking the time to talk to us.

BETH: In an interview, you likened linked short stories to “recognizing someone dear to you in the airport of a faraway city.” Could you explain a little about how you linked the narrator, Failure, and the Corpse together in Failure and I Bury the Body?

SASHA: The book started with Failure and the narrator alone together in a car. I knew they were on a long trip and the landscape they were going to travel—and I had a sense of the emotional tone of the book, and the detritus of the world I wanted to throw in—but I didn’t know what was going to happen. That seemed fine when the poem looked like it would be only a page or two, but as the project grew and grew (and grew), at some point I realized that even though it was made up of these individual poem-sections that are usually only a page long, the whole thing together was actually going to operate more like a novel in stories. So I started asking questions about character and plot arc and the kinds of things that usually only concern fiction writers. I started wondering why the narrator had agreed to go on this road trip in the first place. After all, if a bedraggled, protean stranger with a sketchy past that included genocide and decaying buildings asked you to live in a car with him as you traveled across the desert for heaven knows how long, would you say yes easily? My character had, so I had to figure out why. Once I realized it was largely because of an ex she was trying to get rid of, to bury so to speak, then the idea of the Corpse as character-object seemed obvious. Because I was already working in an allegorical place with this book, I felt no impulse to obscure the Corpse with something less overt. Having him hitchhiking his way into the lives of the narrator and Failure just solved the plot point of how he would he arrive. Plus I like the idea of a corpse in cowboy boots, seated on a trunk, hitchhiking his way across the I-10 or a road like it. Once all three of them were a part of the story, I had to figure out what the book would build to and how it would end. Not to give anything away, but there’s a burial and wedding. I guess in the classic sense that makes this both a tragedy and a comedy.

SASHA: The book started with Failure and the narrator alone together in a car. I knew they were on a long trip and the landscape they were going to travel—and I had a sense of the emotional tone of the book, and the detritus of the world I wanted to throw in—but I didn’t know what was going to happen. That seemed fine when the poem looked like it would be only a page or two, but as the project grew and grew (and grew), at some point I realized that even though it was made up of these individual poem-sections that are usually only a page long, the whole thing together was actually going to operate more like a novel in stories. So I started asking questions about character and plot arc and the kinds of things that usually only concern fiction writers. I started wondering why the narrator had agreed to go on this road trip in the first place. After all, if a bedraggled, protean stranger with a sketchy past that included genocide and decaying buildings asked you to live in a car with him as you traveled across the desert for heaven knows how long, would you say yes easily? My character had, so I had to figure out why. Once I realized it was largely because of an ex she was trying to get rid of, to bury so to speak, then the idea of the Corpse as character-object seemed obvious. Because I was already working in an allegorical place with this book, I felt no impulse to obscure the Corpse with something less overt. Having him hitchhiking his way into the lives of the narrator and Failure just solved the plot point of how he would he arrive. Plus I like the idea of a corpse in cowboy boots, seated on a trunk, hitchhiking his way across the I-10 or a road like it. Once all three of them were a part of the story, I had to figure out what the book would build to and how it would end. Not to give anything away, but there’s a burial and wedding. I guess in the classic sense that makes this both a tragedy and a comedy.

Plus I like the idea of a corpse in cowboy boots, seated on a trunk, hitchhiking his way across the I-10 or a road like it. Once all three of them were a part of the story, I had to figure out what the book would build to and how it would end.

BETH: I was really interested in your use of the myth of Proteus—the sea-god with a mutable form—in Failure and I Bury the Body, and loved how you described Failure as “An Etch-a-Sketch, shaken. / A man in a Proteus box.” Are there certain myths or allegories that you keep going back to as a writer, and if so, why?

SASHA: My school did a unit on Greek myths in 3rd grade and somehow they have never left my marrow. I’m interested in the transformations and mystery of Proteus, so he keeps coming back. He’s just so useful as a metaphor for living, for writing, for love, for language. I’m interested in Persephone and Demeter and how their domestic drama is played out across landscape, even though that doesn’t come into this book at all. And how could any writer not have a bit of a crush on Orpheus, hapless husband that he is?

BETH: One of my favorite poems in the book is “Failure’s Artificial Heart”—it manages to be heartbreaking, surreal, and comic—all at the same time. I’m thinking about the lines

“To receive the heart, first exchange:

Iceberg for the transmitter,

the continuous flow pump;

Mittens for the soft furry shine of the heart’s skin…”

How do you approach the surreal in your poetry? Do you gather specific images, or look to any particular artists for inspiration?

SASHA: Thank you for saying that. I had a number of visual artists in mind as influences for this book—William Kentridge being one of the strongest. I love how the characters in his films absolutely accept the strangeness of whatever happens to them. There is no sense that a room should not be suddenly filling with water or that a landscape shouldn’t melt into a set of birds. If I’ve learned anything from him (and all the other writers and artists who use the surreal in ways that mean something to me), it is that you must absolutely embrace the surreal as what is real inside the space of the poem. If part of you is standing back amused by the juxtaposition of something odd (that old sewing machine and umbrella on an ironing board, for instance), then the poem will feel like a pose instead of a world.

BETH: Reading the book, I was struck by the incredible variance in the visuals of the poem—everything from prose poetry to long, drop-down lines is represented in the book. Did you deliberately try to vary form when you were working on the sequence, or is it something you noticed once the book was completed?

SASHA: I didn’t set out with the goal of having a book with variation, but I did early on decide that the poems could take whatever form felt right to that section’s way of looking at the world. That decision came partially out of a desire to mirror the impulses of the Failure character. In the book, he performs a bunch of odd experiments on the world–knitting with jellyfish tentacles, tethering living hummingbirds to himself to make a coat, etc. I wanted the poems to find the same small impulses to the wild—and to be able to follow them there. Once I decided it was ok to do that, then the question of form became part of how each section progressed through drafts. I think once everything from the road trip started to come in, the poem started to feel large enough to encompass all that range. After all, a road trip is a place where you go from desolate, deserted beauty to signs along a crowded urban highway like the one that says “Non Stop Beautiful Ladies” in El Paso. There is no aesthetic division in how the world happens to you on a road trip. It was really fun to be able to play with form to match that.

BETH: While Failure and I Bury the Body is located in these desolate landscapes of the American Southwest and a melting Antarctica, it ends with the line “We will begin human history, again.” How do you see that emotional progression from fracture to healing in the book?

SASHA: One of the major projects for the narrator in the book is to come to terms with Failure. For me, the larger impulse to that story arc came out of trying to make emotional sense of climate change—how do we live while we are watching a world that is changing—how can we maintain both a sense of calm and a sense of urgency? The characters end up living in a very tender, very small way at the end—outside of cities and with only the old machine of the car as a tent. They almost become nomads as a way to step away from civilization and its effects. In the book, the intimate impulse to the arc came from the ways we all need to understand our own mistakes, our own failures. The narrator’s ability to keep moving—and ultimately to move on to something new that may contain hope—is directly linked to how deeply she embraces and accepts Failure (as both person and idea). I think she sheds the idea of what should be and instead starts living in what is.